To those familiar with his whimsical style of pop art, this statement is obvious. But to the man himself, it’s a statement he resisted to make, and a title many of his contemporaries were reluctant to bestow upon him. “I had trouble with that, says Weidman. “At some point, I said, ‘yeah, I’m an artist,’ but it wasn’t easy. It took awhile. I think it happened because people told me I was. When I got the idea that I had something people wanted, and people started supporting their desire for that by giving me money for it, that’s when I decided, ‘well, I’m probably an artist.’â€Â

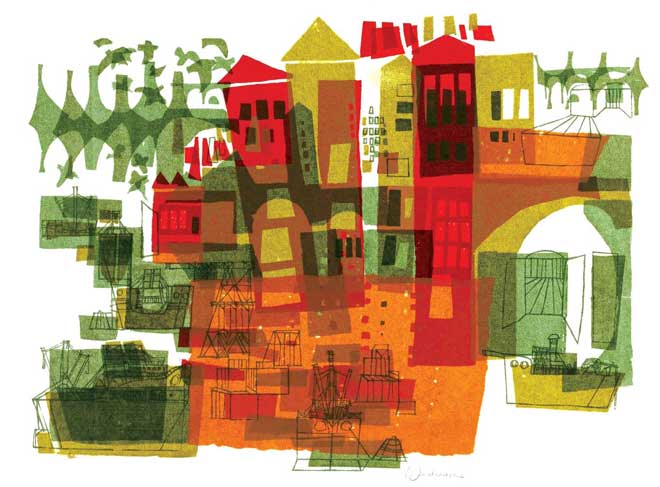

David Weidman’s artwork defines an era in the American public consciousness. It invokes the spirit of the 1970s, of panel station wagons with rear-facing rumble seats, of browning Polaroid photographs, of earth tones with deep oranges, and of the playful undulations of Saturday morning cartoons and nascent family sitcoms. And though he pulled his last screenprint in 1980, FIND caught up with the eighty-nine-year-old Weidman, ever the artist, living content in the same Los Angeles home he build with his own hands in the seventies with the woman who helped him design it, his wife and artistic inspiration, Dorothy. “I started to screenprint because Dorothy decided I would. We were driving in Long Beach seeing all these homes being built and Dorothy said, ‘All those homes have walls that need pictures.’ So I made pictures.â€Â

Born in Los Angeles in 1921, Weidman came of age as an art student at Jepson Art Institute following WWII. It was the height of Disney-era animation and the midst of a booming post-war L.A., where innovation, new ideas, and creativity became an American imperative, with Los Angeles being the epicenter. Under the guidance of master printmaker Guy MacCoy, the Jepson Institute had pioneered many techniques of silkscreen printing as a fine art medium, versus a  reproductive process. Weidman stepped into this new and exciting world of serigraphy and began to embrace it as his preferred medium of expression.

“Screen-printing was a natural, but I didn’t do it the way most people would at that time,†explains Weidman, “They were making a painting or a watercolor or doing something and making a silkscreen of that. My only difference was that I would take an idea and develop it naturally, working best with the characteristics of the medium. So it was not a reproduction of a painting. I developed it on the screen.â€Â

Within Weidman’s editions there are great variations, because unlike most printmakers who aim to reproduce the exact image, with the exact characteristic, Weidman cultivated an organic process in which colors would be remixed, paper stock would change, a new image idea may occur to him. This unique style of improvisational printmaking made, in essence, each print a kind of monotype.

There are so many variations of expression by making marks on paper, and everybody brings to it something different. One of the things you bring to it is your feeling about an object, your emotions, and different people respond differently to different things, says Weidman. “How you organize those elements: line, shape, and color…at some point they result your final outcome. But you can direct your emphasis in different areas. The medium that you’re working in is very important, because different mediums ask for different solutions. All mediums have characteristics that if you’re working well and are aware of them, you can utilize the medium to the fullest. The biggest elements of silkscreen is the overlay and the transparency. If you utilize that, you’re using it in a way that’s honoring to the medium and all that it contributes.â€Â

“You can’t change your character from one moment to the next. There are uncontrollable things that will be inherent in all that you do, but within each area you can insist that the medium takes a role and plays a part.â€Â

Weidman’s time illustrating backgrounds for cartoons such as, “Mr. Magoo, Fractured Fairytales, and Gerald McBoing Boing†really sharpened his awareness of the importance in each medium’s role and how it plays.

“A lot of my maturity came after I left the film industry. In the film industry, we didn’t work in silkscreen. In my mind, the thing I appreciate the most is when I make the medium part of the outcome. I have simple drawings that I made into prints that had little to do with the medium, but then I made prints that depended on the medium for their final essence.â€Â

Weidman gives much of the credit for his artistic style to his wife Dorothy, also a graphic designer. While Dorothy is content to view their relationship as collaborative, Weidman describes it in more stark terms. “You can call it collaborative, or you can call it theiving,” he jokes. “I always steal…thats my big thing.” “She’s a major contributor to my work,†David explains. “She gives me input. She’s a quality designer, and I was taking those and making prints, I added very little to them. Basically, they’re her things. You wouldn’t know the difference between what she influenced me to do, and what was my own.â€Â

“We’re a good pair, because she’s unable to make a salable object. I turn what she does and contributes into something that we can sell together. It’s a total item. If I had to wait for her to come to a total item, I would still be waiting, and I don’t have that long to wait…I don’t have the time!â€Â

Dorothy counters, however, “It goes through his nervous system; it always get his stamp on it,†she explains. “He can take anything and make it work.â€Â

In the 1960s, Weidman opened his own gallery; a modest operation in hip burgeoning gallery district of La Cienega. Pop, Conceptual, Light and Space, were the emergent trends of the times and printmaking, and especially serigraphy, was not considered a fine art medium, yet. Weidman’s work, however, gradually began to shift perceptions of the serigraphy with his following of clients growing rapidly and large, to the chagrin of his fellow gallerists. Soon after, Weidman’s iconic style of illustrative printmaking was being called upon to adorn the lobbies and halls of prestigious hotels across Southern California. His success, however, came with a price. The high physical demands of the process wrought the aging artist, leading Weidman to abandon screenprinting in 1980, leaving only his original prints in circulation.

“When clients began dictating to me the color and the subject, they took me off my rails. They didn’t emanate naturally from where I was…they would disturb my growing and doing…my natural process.†Physically, as well as emotionally, it became way too much.â€Â

Now approaching ninety, Weidman, whose attention in recent years has turned toward ceramics, is not only more comfortable with the idea that he is indeed an artist, but is also reflective on just what that means.

“When I was ten-years-old, without thinking about it, I would reflect the images as I visually saw them. The other approach was to take the elements that make up an object and think about the graphic elements, such as line, shape, and color… these were all elements that became important in the production of the item. That didn’t require any thinking. I was repeating the visual impact from what I was looking at and putting it down on the paper, or canvas or whatever. So, it’s a matter of understanding. Now I can go back and do that, and I can do that very well. It’s important that you’re aware of what you’re doing…that you don’t do it mindlessly. If I make a paining, I don’t think of the outcome and the effect of the painting the same as if I make a silkscreen print. It’s a completely different set of criteria…the importance becomes emphasized on the medium as much as on the image.â€Â

David Wiedman IS an artist…but above all, he’s a man who loves his wife, his family, and his life. It’s this quality, above technique, or notoriety, or commercial success that defines him as such.

“One thing I did at an early age is decide what I wanted to do because it gave me pleasure. And I did it for those reasons. When it stopped being pleasure, is when it became a business, and then it lost its appeal to me. So do what gives you pleasure. The more you do, the better you WILL get.â€Â